General Notes

If I had to give it a grade it would be near-optimal to leave some space for the unknown. If you like mathematics and a good story you will love this book.

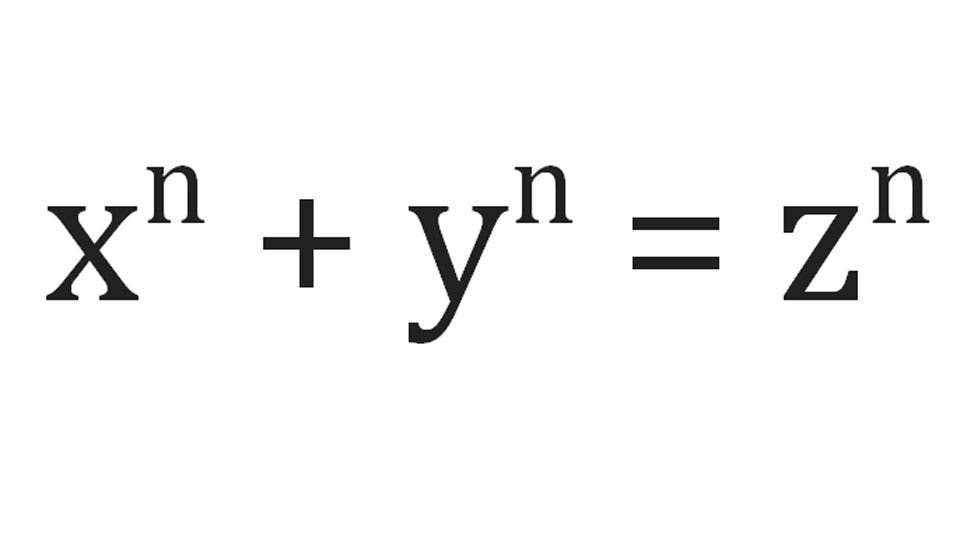

Simon manages to make a book about a mathematical theorem approachable by anyone with English knowledge. The book starts way before Fermat’s birth in ancient Greece, some may say that’s a big digression from the main subject, but still marvelously connected with how Fermat was able to study mathematics and how was his thinking when solving mathematical problems. Through the years much exceptional mathematics made their contributions towards a solution, but nothing definitive was proposed as the solution to this intriguing puzzle. The theorem is quite easy to understand, young Andrew Wiles the man who later would find a solution stumbled upon the theorem as a child, it states that: no pair of numbers raised to a power higher than two can add up to a third number raised to the same power. This simple statement remained unsolved for more than 300 years and this book is a great overview of how one of the finest puzzles of modern history was solved.

Summary Notes

Origins

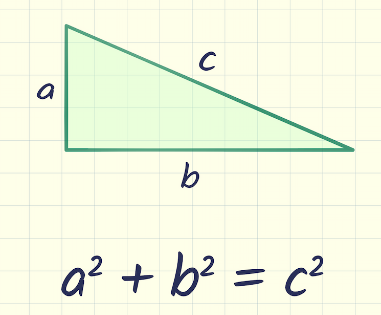

- The last theorem has its origins in the mathematics of ancient Greece, it links the foundations of mathematics created by Pythagoras.

- Pythagoras gained his mathematical skills on his travels throughout the ancient world. He learned most of his mathematical skills with the Egyptians and Babylonians, both peoples that had gone beyond the limits of simple counting and were capable of performing complex calculations that enabled them to create sophisticated accounting systems and construct elaborate buildings.

- These civilizations used mathematics as a recipe, a tool to aid them in practical endeavors, what was important for the civilizations was that a calculation worked — why it worked was irrelevant.

- Pythagoras found a place to settle and created a Brotherhood, a religious community, and one of the idols they worshiped was Number. They believed that understanding the relationships between numbers could uncover the spiritual secrets of the universe and bring themselves closer to the gods.

- Pythagoras was also intrigued by the link between numbers and nature. He realized that natural phenomena are governed by laws and that these laws could be described by mathematical equations. One of the first links he discovered was the fundamental relationship between the harmony of music and the harmony of numbers.

- This devotion to number lead Pythagoras to create Pythagoras’s theorem and prove that it is true for every right-angled triangle, creating a universal law of mathematics. This theorem will forever be associated with Pythagoras, it was used by the Chinese and the Babylonians one thousand years before. However, these cultures did not know that the theorem was true for every right-angled triangle.

- Here, I should highlight the search for a mathematical proof, Pythagoras discovery was the beginning of absolute knowledge, an ultimate truth, an infallible foundation. This search continues until drives mathematicians today.

Fermat’s Last Theorem

- Pierre de Fermat was a man in the Renaissance tradition, who was at the center of the rediscovery of ancient Greek knowledge, but he asked a question that the Greeks would not have thought to ask, and in so doing produced what became the hardest problem on earth for others to solve.

- Fermat was an interesting man. Although he was not a mathematician by profession (he was a member of Parlement of Toulouse), he dedicated a lot of his time to mathematics. As the book s says: “He would write letters stating his most recent theorem without providing the accompanying proof. Then he would challenge his contemporaries to find the proof. The fact that he would never reveal his proofs caused a great deal of frustration. René Descartes called Fermat a ‘braggart’”.

- After his death, one of his study books were found with some annotations on the margins: “It is impossible for a cube to be written as a sum of two cubes or a fourth power to be written as the sum of two fourth powers or, in general, for any number which is a power greater than the second to be written as a sum of two like powers”. He continues: “I have a truly marvelous demonstration of this proposition which this margin is too narrow to contain”. Here’s Fermat’s enigma.

- Fermat’s last theorem is formally stated as:

- For n > 2

A travel through the story of mathematics

- Simon takes us through the journey of all the contributions from the many mathematicians to solve Fermat’s theorem.

- We learn how complex numbers were introduced and how Euler used them to try to prove the theorem for n = 3. We also learn about prime numbers and that to prove the theorem for all number we would only need to prove it for the prime numbers, Euler’s proof for the case n = 3 automatically proves the cases n = 6, 9, 12, 15, … and so on.

- Sophie Germain, Gustav Lejeune-Dirichlet, and Adrien-Marie Legendre also contributed by proposing a general approach to the problem, which proves for the case n = 5. Gabriel Lamé made some further ingenious additions to Germain’s method and proved the case for the prime n = 7.

- In the way, we learn about the power of an invariant. This by its own would give an extraordinary blogpost.

- With the advent of computers teams of computer scientists and mathematicians proved the Last Theorem for all values of n up to 500, then 1,000, and then 10,000. More recently mathematicians could claim that Fermat’s Last Theorem was true for all values of n up to 4 million. However, this doesn’t assure the truth of the theorem, one example mentioned in the book is:

Euler claimed that there were no solutions to an equation not dissimilar to Fermat’s equation: x4 + y4 + z4 = w4. For two hundred years nobody could prove Euler’s conjecture, but on the other hand, nobody could disprove it by finding a counterexample. First manual searches and then years of computer sifting failed to find a solution. Lack of a counterexample was strong evidence in favor of the conjecture. Then, in 1988, Naom Elkies of Harvard University discovered the following solution: 2,682,4404 + 15,365,6394 + 18,796,7604 = 20,615,6734. Despite all the evidence, Euler’s conjecture turned out to be false. Elkies proved that there were infinitely many solutions to the equation. The moral is that you cannot use evidence from the first million numbers to prove a conjecture about all numbers.

There was no reason for Fermat’s Theorem to be any different from Euler’s conjecture, extending the mystery around the theorem.

A turn of the destiny

- Some years after Lamé proving the theorem for n = 7, Wolfskehl would make a major contribution to finding the proof of the Last Theorem. Wolfskehl was in love with a beautiful woman, who rejected him to the point that he decided to commit suicide. He planned his death with meticulous detail but completed it slightly ahead of his midnight deadline. To wait for the cutoff of his life he went to the library and began browsing through the mathematical publications.

- Soon after proving the theorem for case n = 7, Lamé and another mathematician Augusting Louis Cauchy proclaimed that they were both close to proving Fermat’s Last Theorem. This announcement caused a commotion in the mathematical community. However, both were proved wrong by Ernst Kummer, he argued that both were heading toward the same logical dead end.

- This was the book Wolfskehl found himself reading moments before his death, Kummer’s classic paper explaining the failure of Cauchy and Lamé. It was one of the great calculations of the age, imagine his surprise when he saw what appeared to be a gap in the logic — Kummer had made an assumption and failed to justify a step in his argument. In the morning the suicide plan was left behind and he went out to share his discovery with his pears.

- Years later, Kurt Gödel proved that mathematics could never be logically perfect, and implicit in his works was the idea that problems such as Fermat’s Last Theorem might even be impossible to solve. Creating something called: theorems of undecidability.

The beginning of the end

- Started when a link was made between Fermat’s Last Theorem to the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture, by turning Fermat’s equation into an elliptic equation. All the leap is extremely interesting and worth the read but the short version is (quoting here, so you are no misled by my words):

Frey’s argument was as follows:

- If (and only if) Fermat’s Last Theorem is wrong, then Frey’s elliptic equation exists.

- Frey’s elliptic equation is so weird that it can never be modular.

- The Taniyama-Shimura conjecture claims that every elliptic equation must be modular.

- Therefore the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture must be false!

Alternatively, and more importantly, Frey could run his argument backward:

- If the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture can be proved to be true, then every elliptic equation must be modular.

- If every elliptic equation must be modular, then the Frey elliptic equation is forbidden to exist.

- If the Frey elliptic equation does not exist, then there can be no solutions to Fermat’s equation.

- Therefore Fermat’s Last Theorem is true!

Andrew Wiles proved the Taniyama-Shimura conjecture: Every single elliptic equation can be correlated with a modular form, which was enough to imply Fermat’s Last Theorem. The rest of the book is the exciting history of how.